The walk along Havana’s Malecón seawall-promenade is long. One can set out from the moat of the renaissance Castillo Real de la Fuerza, in and out of the crumbled arcades of 19th century neo-classical townhouses, pass below the faded American colonialism of the 1930’s Hotel National de Cuba, onward past mafioso Meyer Lansky‘s chi chi Hotel Riviera Habana, and then a little beyond to the the super-hip nightclub/gallery Fabrica de Arte Cubano, and you’d have traveled a distance of 5 miles and crossed four and a half centuries of cultural geography.

Illustrated on the left a 16th century map of Havana with the four-point Castillo de Real Fuerza guarding the Harbor of Havana like a God’s Eye. On the left of the map the future Malecón would run down the coast , facing north to Florida. On the right above, a fashion show at Fábrica de Cubano, “a laboratory of interdisciplinary creation” located in a re-purposed oil factory.

Along the Malecón, the wind picks up in the late afternoon, and it’s a hot wind. Abbe and I are wiped out. At 4 pm in April its hot, glary and dusty. We’re hungry and thirsty. We crash at an open-air cafe for a beer and squint at the menu board lost in a bleary-eyed translation. Checking out our neighbors food, we exchange smiles with the guys across the table. Two buddies from the University of Havana, Ernesto is treating Vicente to beer, celebrating his birthday with Bucaneros Fuertes.

Soon we’re buying each other beers–building a bridge across ages, income levels, and economic systems. Two beers in, I am trying to explain the jokey concept of a “first world problem” in my miserable Spanish … something about different cultural expectations in Havana vs San Francisco. I plow on, while realizing I should just shut up—not good, not funny, this capitalist irony of mine in an impoverished communist country. Ernesto is making the point about how successful Cuba is; it’s definitely not a third world country –whatever that means. As I scramble to remember and explain the history of the Cold War from an American–scratch that–from an U-S-A perspective, Ernesto is quick to point out how much more successful Cuba is than Mexico and how much more safe, sensible and civic than the image of the US he sees on smuggled DVD’s of American TV shows. He goes on, “Here in Havana there’s no drugs, no guns, no homeless.” And while I can easily separate TV show fantasy from reality at home, here in Havana the TV image is our primary representation and who we really are. I shake and fist-bang my head. It’s all true, I admit. Everything you see on TV, it’s exactly true.

Soon we’re buying each other beers–building a bridge across ages, income levels, and economic systems. Two beers in, I am trying to explain the jokey concept of a “first world problem” in my miserable Spanish … something about different cultural expectations in Havana vs San Francisco. I plow on, while realizing I should just shut up—not good, not funny, this capitalist irony of mine in an impoverished communist country. Ernesto is making the point about how successful Cuba is; it’s definitely not a third world country –whatever that means. As I scramble to remember and explain the history of the Cold War from an American–scratch that–from an U-S-A perspective, Ernesto is quick to point out how much more successful Cuba is than Mexico and how much more safe, sensible and civic than the image of the US he sees on smuggled DVD’s of American TV shows. He goes on, “Here in Havana there’s no drugs, no guns, no homeless.” And while I can easily separate TV show fantasy from reality at home, here in Havana the TV image is our primary representation and who we really are. I shake and fist-bang my head. It’s all true, I admit. Everything you see on TV, it’s exactly true.

April before last we had the good fortune to fly into Havana from Fort Lauterdale between Obama’s opening and Trumps closing. There was still leftover excitement from Obama’s presidency and unease about what Trump might yet do.

A UNESCO heritage site, Havana is spectacular in decay. Like other historically preserved cities, Havana benefits from boom times followed by periods of neglect and isolation. The isolation of a half century of American embargo is tossed into casual conversation like the hot weather, an internalized piece of cultural identity that just is. (“It’s very difficult here, but at least we’re happy,” according to our Airbnb host.) Without access to support and investment from the US (1962 embargo ), the collapse of Soviet Union (1988) and lately the crash of Venezuela oil (2015-7), Cuba, especially Havana particularly, has become increasingly reliant on the international investment of UNESCO and the international tourist industry.

We came attracted by the romance of an architecture in decay and a history, literally collapsing. And we came to Havana in order to witness the influence of increased tourist-related investment in Cuba as it challenges historical and cultural preservation and the communist system itself. Whether by investment or neglect, today’s Havana was changing. Much more than we expected, Cuba’s serious cultural isolation affected us as well, providing a flipped perspective of ourselves and our values.

We came attracted by the romance of an architecture in decay and a history, literally collapsing. And we came to Havana in order to witness the influence of increased tourist-related investment in Cuba as it challenges historical and cultural preservation and the communist system itself. Whether by investment or neglect, today’s Havana was changing. Much more than we expected, Cuba’s serious cultural isolation affected us as well, providing a flipped perspective of ourselves and our values.

Back at La Abadia Cafe Ernesto insists on buying us beer as he drives home his point: “There are three great things about Cuba.” I know I know, I interrupt, uh Healthcare, Education and Music, right? “Music? No, not music. Security!” Oh … and then music, right. “Ok, then music.”

Ernesto was right about security. There was a clear street presence of unarmed foot police, young women, men, black, white—very mixed and apparently in a system with some structural equality for sexes and races. In San Francisco, we can rationalize our suspicions as street smarts. In Havana, the part we saw, it’s different; cynicism and suspicions aren’t useful. Instead we two senior-ish Americans walk the dark, unlit streets of a ruined cityscape, a deteriorated infrastructure, surrounded by poverty, without fear, comfortable in the warm night air and very friendly people.

Frequently, we’re approached by locals telling us about their aunt in Vancouver or New Jersey or recommending their friends restaurant or offering to pose with us—and sometimes asking for some help–it is very difficult here—and sometimes offering a cigarette or restaurant advice or plugging their earphone in my ear so I can enjoy the music on their i-pod. The tourist-local dynamic can get weird. In Havana Vieja, a laughing foreign tourist tosses candy up to laughing children on balconies above. And while we can easily afford a 5-hour taxi to the tourist resort town of Trinidad, along the highway we pass a local holding up two pesos for a lift, while another holds up two potatoes. Making sense and creating a clear picture of what is happening in Cuba given competing online viewpoints and differences in internet access is challenging. On the one hand, the controlled views of the Cuban State offer little critical analysis or detail online, and on the other, Cuban emigre’s in nearby Florida present a barage of information, expressing an intensely complicated emotional attachment to a lost homeland.

It would be naive to think security and the quaintness of global isolation didn’t come at a price. The scenic Malecón becomes a riot scene in this video of a 1994 protest during the “Special Period” when the end of Soviet support led to extreme austerity and the refugee crisis of the balseros or boat people.

It was getting dark now. Ernesto and Vicente had taken off, We finished up our beer and left the cafe, crossed the highway and sat on the seawall facing the Florida Keys, 90 miles away. My head was buzzing. Waves crashed the seawall and tossed around us like in an open boat–90 miles to the Florida Keys and then just beyond, the gigantic mainland, rich, powerful, consuming, controlling, proud, indifferent.

It’s late, waves crash, locals are cooling off. A 5 year-old jumps up and sits next to me, smiling. He doesn’t understand my poor Spanish. He’s smiling big. His family 10’ further down the wall smile at me. Everyone seems happy and our differences and divisions seem not so apparent, not to me, and definitely not useful. I smile back. The wind feels good.

You cannot see the mainland from the Malecón, but you can see both from a satellite. Below in a Nasa image of Cuba, the bright tongue of the Florida Keys leads from Miami downward to Havana.

Thanks to Olimpia Niglos and the Spain’s Archivo General de Indios for the plan view of early Havana, and also thanks to Ernesto and Vicente for sharing beer and points of view.

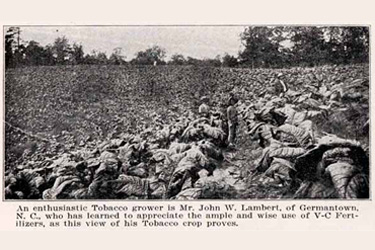

McDaniels was saddened to see that trees and grass had been allowed to flourish, and the quarters themselves prettied up when compared to his memory on first encounter of the dilapidated share-cropper houses, the dusty dirt road and tobacco fields. “There should be dirt instead of grass here, and there it should all be open fields. You should be able to see the relationship between the slave quarters and the overseer’s house.”

McDaniels was saddened to see that trees and grass had been allowed to flourish, and the quarters themselves prettied up when compared to his memory on first encounter of the dilapidated share-cropper houses, the dusty dirt road and tobacco fields. “There should be dirt instead of grass here, and there it should all be open fields. You should be able to see the relationship between the slave quarters and the overseer’s house.” Memories are colored by what we understand and imagine as much as what we’ve seen. How do we choose to remember this past (1) from a place of beauty and comfort connecting intellectually or (2) as a miserable visceral experience of heat, dust and overcrowding–a physical reenactment of a particular moment in the past. Which moment, the darkest?–the most heroic–the most beautiful? Judging from the recollections of the ancestors, collective memory, unlike personal, is complex, not selective, encompassing a wealth of feeling, dark and bright, both profound. It should be noted that some slaves’ recollections have included fond memories of masters, mistresses, and home while others, less favored, feel disgust. While descriptions of the benign re-enactments at Williamsburg seem odd pantomimes, the unconditioned heat and cold and lack of light of NYC’s Tenement museum are real sensations that truly deepens understanding. Barring literature and cinema’s artistic license (Tarantino’s

Memories are colored by what we understand and imagine as much as what we’ve seen. How do we choose to remember this past (1) from a place of beauty and comfort connecting intellectually or (2) as a miserable visceral experience of heat, dust and overcrowding–a physical reenactment of a particular moment in the past. Which moment, the darkest?–the most heroic–the most beautiful? Judging from the recollections of the ancestors, collective memory, unlike personal, is complex, not selective, encompassing a wealth of feeling, dark and bright, both profound. It should be noted that some slaves’ recollections have included fond memories of masters, mistresses, and home while others, less favored, feel disgust. While descriptions of the benign re-enactments at Williamsburg seem odd pantomimes, the unconditioned heat and cold and lack of light of NYC’s Tenement museum are real sensations that truly deepens understanding. Barring literature and cinema’s artistic license (Tarantino’s  There is clearly a place for the imagination, intellect and emotion to fill the empty structures whose history is corrupt, but whose form intact. Horton Grove and Drayton Hall’s emptiness provide a clear and simple example of the unfurnished historic structure as a vessel for memory.

There is clearly a place for the imagination, intellect and emotion to fill the empty structures whose history is corrupt, but whose form intact. Horton Grove and Drayton Hall’s emptiness provide a clear and simple example of the unfurnished historic structure as a vessel for memory.